The Gum Wall Hall of Fame: Franz Kafka - Guest Post by LiteraryMinded

‘In the Penal Colony’

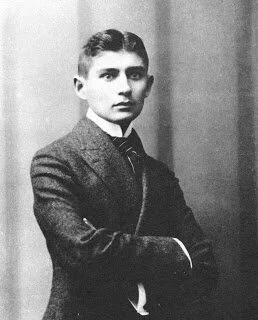

Franz Kafka

After visiting the Kafka museum in Prague (detailed in this blog post), I decided I must and would read everything Kafka had ever written.

It’s one of the best decisions I’ve ever made. Not only was I enraptured by his fiction, notebooks and diaries; I felt an intense affection for, and even affinity with, the author who felt he was ‘literature and nothing else’, whose ‘fear’ was his substance – his tortuous, complex inner life (and vivid dreams); and his intense sensitivity to contradiction and forms of oppression, real and imagined.

It’s difficult to choose just one of his affecting, off-kilter short stories to talk about. Among my favourites are ‘The Judgment’, ‘The Metamorphosis’ (its brilliance is not exaggerated), ‘A Country Doctor’ (influential for my writing), ‘A Report to an Academy’ (and in fact, all his animal stories) and ‘A Hunger Artist’ (haunting). And these are just his longer stories. Many of the shorter works and fragments also appeal, featuring moments of unraveling, sadomasochistic drives, nonsensical time, more intuitive animals, interrupted solitude and more.

But ‘In the Penal Colony’ is the story I would cite as my favourite. It is odd, cruel, fascinating, sad and unresolved. An impartial explorer is visiting a penal colony and being shown an apparatus for torture. The officer showing him passionately explains the machine’s function and purpose. The machine used to be an entertainment, a spectacle (even for children), and now no one comes to watch the executions. It is supposed to write ‘exquisite’ justice onto the victim’s body. The officer shows the explorer the ‘script’, which is used by the ‘Designer’ (part of the machine), and the explorer cannot interpret it:

‘”Yes,” said the officer with a laugh, putting the paper away again, “it’s no calligraphy for school children. It needs to be studied closely. I’m quite sure that in the end you would understand it too. Of course the script can’t be a simple one; it’s not supposed to kill a man straight off, but only after an interval of, on an average, twelve hours; the turning point is reckoned to come at the sixth hour. So there have to be lots and lots of flourishes around the actual script; the script itself runs around the body only in a narrow girdle; the rest of the body is reserved for the embellishments…”’

The turning point – a kind of absurd awakening to suffering? Where the condemned person loses their resistance to the end that is coming? ‘Nothing more happens than that the man begins to understand the inscription, he purses his mouth as if he were listening.’

The condemned, on whom the machine is supposed to be demonstrated, has been arrested for sleeping on the job, and instead of apologising, grabbing his master’s legs, shaking him, and saying something nonsensical. It is explained to the explorer, too, that the condemned man does not know his sentence (and has obviously not been given the chance to defend himself). So there is the common Kafkan theme of injustice.

An unknowable and remote power is also in the story, as it is in other Kafkan works, such as The Castle. In this, it is the old Commandant, who ran the penal colony in its heyday of spectacle-punishment, and whom the officer fears. The officer reflects on those old times of glowing, popular punishment: ‘“…How we all absorbed the look of transfiguration on the face of the sufferer, how we bathed our cheeks in the radiance of that justice, achieved at last and fading so quickly! What times these were, my comrade!”’

I won’t ruin the ending (because it’s a must-read), but things take an unexpected, squeamish turn. It’s a confronting story, one you won’t forget anytime soon.

The last thing I’ll mention is the way Kafka manages to inject his sentences with a seductive and vivid strangeness – describing things that are only just off the spectrum of normality. You can see why his imagination would have both driven and tormented him. A line that sprung out on re-reading, where the officer is still comparing the differences between the good old days and the present, was: ‘“…Anyhow, the machine is still working and it is still effective in itself… And the corpse still falls at the last into the pit with an incomprehensibly gentle wafting motion, even though there are no hundreds of people swarming around like flies as formerly…”’ The incomprehensibly gentle wafting motion of the body is made comprehensible. This is how many of his narratives work, such as The Trial, where characters explain (or unexplain) something until it is fact. And of course this comes back to notions of the constructions of power, and by entities of power (again real or imagined), and is one reason Kafka’s stories are ever-relevant.

Angela Meyer’s short fiction, reviews and articles have been published widely. She is a former editor of Bookseller+Publisher magazine. She chairs panels at many writers’ festivals, teaches workshops on blogging and social media, and is currently undertaking a Doctor of Creative Arts. Her popular blog LiteraryMinded has just turned three.