Endtime

My father, Dr Duncan Steed, died on April 17, 2023, just under a week shy of his seventy-eighth birthday. The plan, I think, was for me to write about my dad and then we’d celebrate him while he was still around to see it.

It was in hindsight, an ill-conceived plan, made all the more problematic with each subsequent hospital visit after the first emergency visit (at least, in his last run of stays) in 2020, and the increasing precariousness of his life. I had his words, his voice, and his memories floating around and around in my head, to the point that it felt that he was always going to be OK. Still, there was no way we were ever going to outrun mortality.

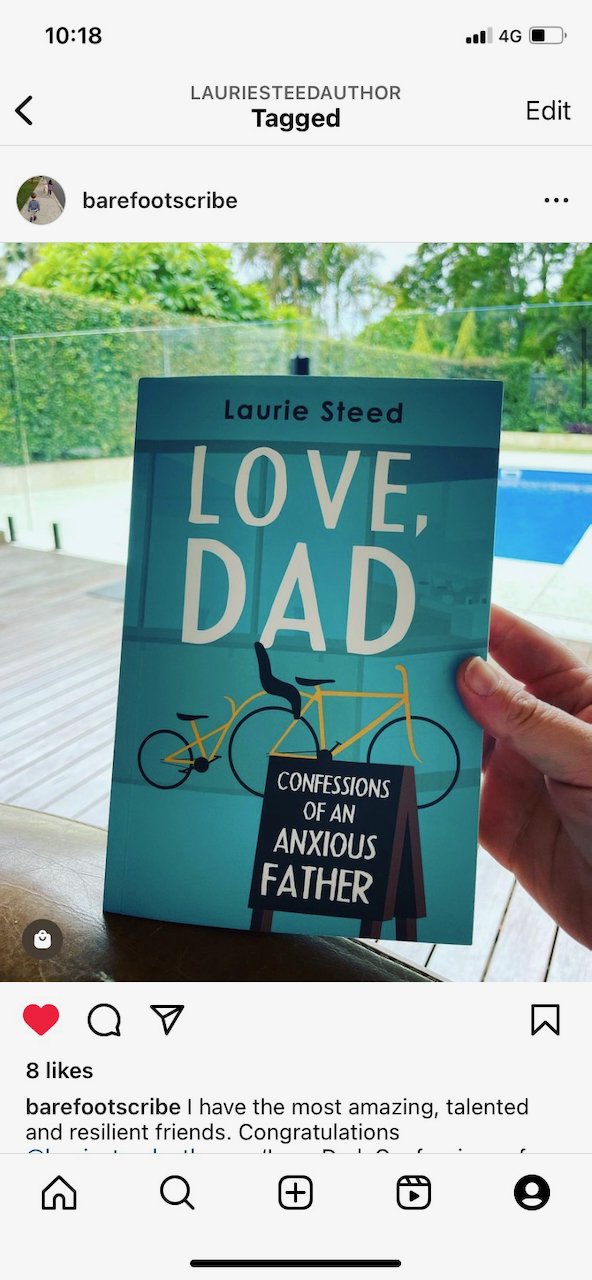

It feels weird without my dad, but with, Love, Dad, a book that honours and acknowledges his memory. ‘Heartbreaking’ describes that space. But then, so does ‘comforting’, for what better way to remember someone than to have written about them just prior to their death? I already knew writing was a genius way to process grief, as in 2004, just after my father’s first heart attack and subsequent survival, I wrote a book, Nevermore, about a young man who’s terrified of losing his father, only to lose his father by the end of the novel. That now sounds eerily like Love, Dad, although it didn’t until just under six weeks ago.

Really, all of this shit is just weird. I picked up my copy of Love, Dad from Fremantle Press on the day Dad died. The day after that, I went up to his house. He has (had) every manuscript I’ve written, including Nevermore (although I’d retitled it Nearly Lost You by the time he got the hard copy. Anyway, I leafed through it, because, well, I wasn’t particularly enjoying packing up his things. On the last page of that book, finished seventeen years prior, there’s a letter from the dad in the book to the son. The last two words are, ‘Love, Dad.’

Or maybe I am scrambling for meaning wherever I can find it. As part of packing up his things, my sister said I could take a keepsake; something meaningful for me. I took a giant Letter ‘D’ I’d once bought him, and an article I’d written for The Big Issue about the two of us playing Scrabble together. They’re on my bookshelf now, They say, We were here. They plead for more time when it’s clear that the clock has already stopped.

I am acutely afraid that people who are currently reading Love, Dad will start off strong, enjoying the book, and wanting a laugh from their funny, friendly mate. Only then I necessarily take them down into some of the toughest years of my life amidst moments of joy or laughter. I can’t and don’t want to apologise for those more personally challenging events and experiences being an integral part of that book; I am still fearful that it all will be a little too real for some people, though.

So, why write a book like Love, Dad? Because guys are really good at ‘carrying on’ with our lives, even when we’re far from OK. We feel all kinds of things bubbling beneath the surface, but convince ourselves that really, we don’t. So, things come out in weird ways. We smash a pizza in one sitting. We start to drink a little more until our little more is a great deal more. We excercise like lunatics. We lose ourselves in sex, or video games or lists or great albums or anything that does not require us to feel such diffult emotions or notions of vulnerability.

I wrote Love, Dad because someone needs to say, ‘Life can sometimes be really fucking tough.’ I wrote Love, Dad because in spite of me having a great dad, and in spite of all my attempts to be a great dad, it is still sometimes hard to not just freak out about one’s inability to deal with life on life’s terms.

My only way out is and has always been connection, authenticity and shared vulnerability, as found through my writing. There was once a time when I thought I was insane, even as I wrote my words.

But, no longer, because my dad told me more than once I was ‘perfectly normal. A little neurotic, perhaps, but then isn’t everyone?’

My father, Dr Duncan Steed died on April 17, 2023, just under a week shy of his seventy-eighth birthday. I asked my son, Noah, what he would say to my Dad if he were still around. He said, ‘I love you, Grumpy.’ I said, ‘You know what he would say to you if he were still around? He’d say, “I love you, Noah,”’

Noah is in Love, Dad too because it’s hard to write a book about dad without mentioning sons. I am glad he’s in the book. Indeed, having him in there is like seeing a colourful balloon float by on anotherwise grey day. It is hard to write a book when your dad has just died. It is nice to know he’s in there, though, awake, alive, and warm to the touch.

When editing the book, my editor Georgia often seemed to sense when I was being declarative or convergent where I needed to stay in a state of limbo. These scenes were often scenes in the book with my dad; she made me stay, had me get real about my father’s impending death and how already it was opening me up to greater emotional experiences.

What would I say to my dad if he were still around?

Nothing.

Everything.

Or maybe I’d just listen.